We look for the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come. Amen.

The Nicene Creed

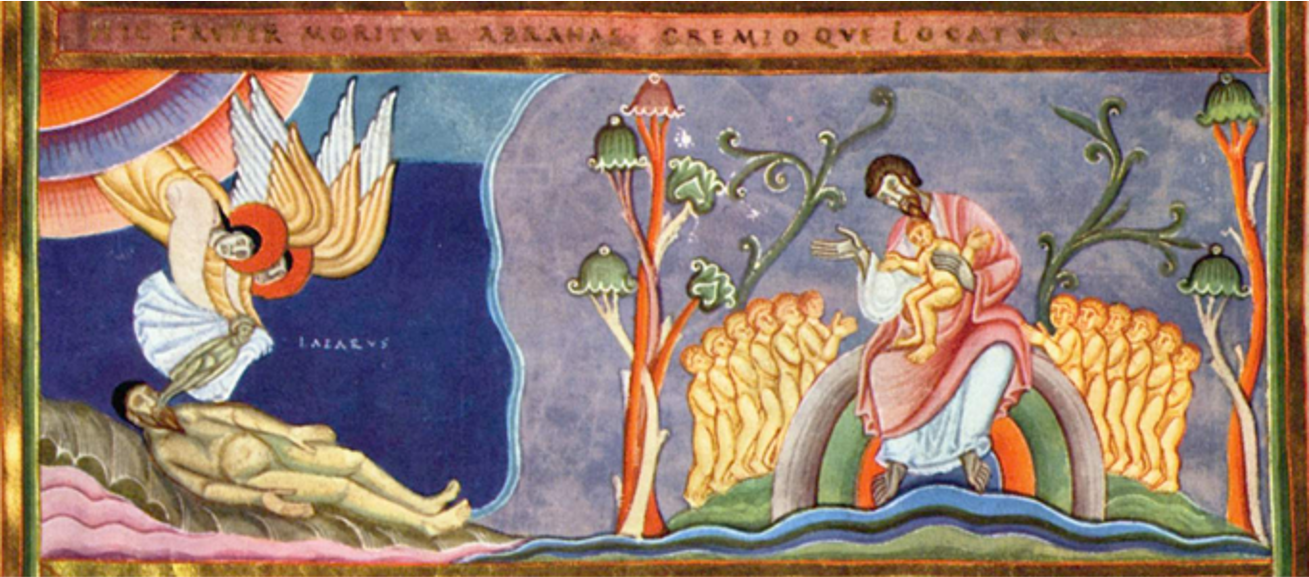

The poor man died and was carried by the angels to Abraham’s side. The rich man also died and was buried, and in Hades, being in torment, he lifted up his eyes and saw Abraham far off and Lazarus at his side. (ESV) Luke 16:22–23

To be sure, the Gospel concerns itself with eternity among other things. It tells the truth about life being something not limited to what we live in this vale of flesh. We look forward to the life of the word to come, we say in the creed. But Scripture also makes it clear that the life to come is decidedly more pleasant for some than for others. As in the story of Poor Man Lazarus, some will spend eternity at the side of Father Abraham , while for others, like the rich man, the world to come will be a place of torment.

The elect and the reprobate. The saved and the lost. Those who receive salvation by grace – God’s unmerited favor – through faith, and those who receive the punishment due us all. The modern mind is often at a loss when it comes to life in the world to come, but even when it accepts the proposition, it prefers to see all humanity as part of the “some” like Poor Man Lazarus or to simply cancel the idea of eternal torment. Reprobation does not exist but as a temporary state while things work themselves out to a happy ending.

Marilynne Robinson is a Pulitzer Prize winning author. For the past fifteen years she has told us stories from a fictional Iowa farm town call Gilead (Gilead, 2005; Home, 2008; Lila, 2015; and now Jack, 2020). Robinson is a modern – or maybe she is not modern – who accepts the Creed and finds John Calvin to be helpful in her understanding of Scripture and of life.

In Jack, the latest in the Gilead series, Robinson reflects on reprobation, but not much on the vexing question of election. A couple of notes: Jack is best read after reading the first three books in the series. You may wish to Google a review of the book, but beware. Jack is set in early post-World War II St. Louis, and the hideous reality of Jim Crow is central to the story. But too many reviewers assume racism to be the theme of the book, some even criticizing Robinson or Jack, the character she creates, for being insufficiently woke. That is to miss the depth of Robison’s reflection on grace and life in this world.

Jack is a story all about grace, but not the special grace by which some are redeemed, joining Poor Man Lazarus in the life to come. It is about common grace, or general grace, the kindness of God poured out in this life on all humanity, by which, for instance, the rain waters the earth, falling on the just and the unjust alike.

In the story, Jack, a pastor’s son, acknowledges his reprobation; he has lived it and he has experienced its disastrous effects in his life. Jack is not interested in denying his identity as a reprobate. Robinson does not ask us to question Jack’s self-assessment, nor is she inclined to contemplate the mysteries of election or the possibility that Jack may yet encounter the amazing grace that saves wretches like him.

Jack is not particularly wicked (his wretchedness is of the petty sort) or unlikeable. He is lost. He is a prodigal who has yet to leave the far country. He has no sense that he might do better as a servant in his father’s house let alone that his father might call for the best robe and put a ring on his finger.

In the story Marilynne Robinson tells, common grace touches Jack’s life through a chance encounter with Della, a black woman and a pastor’s daughter. Della is kind and good and seems to know both common and special grace. Jack and Della fall in love and Jack sees the possibility of something other than wretchedness. But Jack is white and Della is black, and in Jim Crow St. Louis their love is illegal if not impossible.

I won’t tell you how the story ends, but it is not a story of redemption so much as a story of common grace. Della is the means by which God’s grace, common as it is, touches the life of a reprobate. That’s what we must know about the story of Jack.

For good reasons, Christians love to sing songs and tell stories about amazing grace, stories of redemption and of our hope for the world to come. Keep singing songs. Keep telling stories. Amazing grace is God’s business, however. It is not ours to speculate as to the mystery of election. But common grace may be our business. Our love, care, and concern, our good and kind works, may be means of common grace even in the life of a reprobate. And that is amazing. Who knows what God might make of that common grace.

Our post-election world is in desperate need of grace, the common grace of love and kindness shown to all. Perhaps those of us who know amazing grace could allow ourselves to be used of God as means of common grace. That would be amazing.