I have been thinking about evangelism. Our denomination has made evangelism one of its top strategic priorities. We keep hearing the tagline, “Put the ‘e’ back in EPC,” meaning evangelism, I think. Our leaders may have forgotten that there is a difference between the broad and rich term “evangelical” and the narrower term “evangelistic.”

That is not to say that evangelism is not a good thing. Evangelism is, according to the Evangelical Dictionary of the Bible, “the proclamation of the good news of salvation in Jesus Christ with a view to bringing about the reconciliation of the sinner to God the Father through the regenerating power of the Holy Spirit.” Sounds good to me. Yes, evangelism is about much more than getting people – by whatever means – to ask Jesus into their hearts.

In our Reformed Tradition we talk about our “effectual call.” The God who knew us and loved us “before we were formed in the womb” (Jeremiah 1:5), calls and claims us in Christ. The Westminster Confession speaks of those who are effectually called this way: “(God) calls them by his word and Spirit out of their natural state of sin and death into grace and salvation through Jesus Christ. He enlightens their minds spiritually with a saving understanding of the things of God. He takes away their heart of stone and gives them a heart of flesh. He renews their wills and by his almighty power leads them to what is good. And so he effectually draws them to Jesus Christ. But they come to Jesus voluntarily, having been made willing by God’s grace.”

That is the theological backdrop to how I answer the evangelistic question of when and how I became a Christian. I would prefer the question to be, “When and how did you experience God’s effectual call in your life?” I know, the Four Spiritual Laws and Three Circles crowds may not like my question.

My answer to the question of the when and how of my effectual call takes me back to January 1970, and the beginning of the winter quarter of my freshman year at the University of California at Santa Cruz. I returned to campus eager for the new term, but anxious about the loneliness I had experienced in the fall term and confused by the chaos – the 60s had just ended – in the world around me.

Within a few days of my return, a dormmate, Calvin by name, invited me to worship at the First Presbyterian Church. It seemed safe enough, though I would suddenly be exposed to a group of Christians unlike any I had known in my growing up Presbyterian Church.

Calvin’s invitation was no accident. His friendship and the wonderful fellowship at First Presbyterian Church have always been clear in my mind. God used them for his effectual call in my life. The loneliness and confusion of the fall quickly dissipated as God’s call became effective that winter.

But it turns out that something else was going on, something I’d nearly forgotten.

The college required all first-year students to take a core course on Western Civilization. The professor who normally taught the course during winter quarter was on sabbatical, so a guest lecturer from the U.K. led the class. Mr. Nicholl, we called him because the campus was self-consciously egalitarian and famously non-conformist. None of our professors were addressed as “Doctor,” no matter how many PhDs they may have earned. Mr. Nicholl’s lectures on Medieval history were captivating. He used no notes and often closed his eyes when he spoke as if it helped bring his knowledge and wisdom to the fore.

Though it was a state university and famously non-conformist, those who designed our core course in Western Civilization knew we’d have to know something of the Bible to understand the legacy of the West.

I had nearly forgotten the role Mr. Nicholl’s lectures played in my effectual calling.

My mother saved the letters I wrote home during my college years. I went through them recently and came across one written barely two weeks into winter quarter 1970:

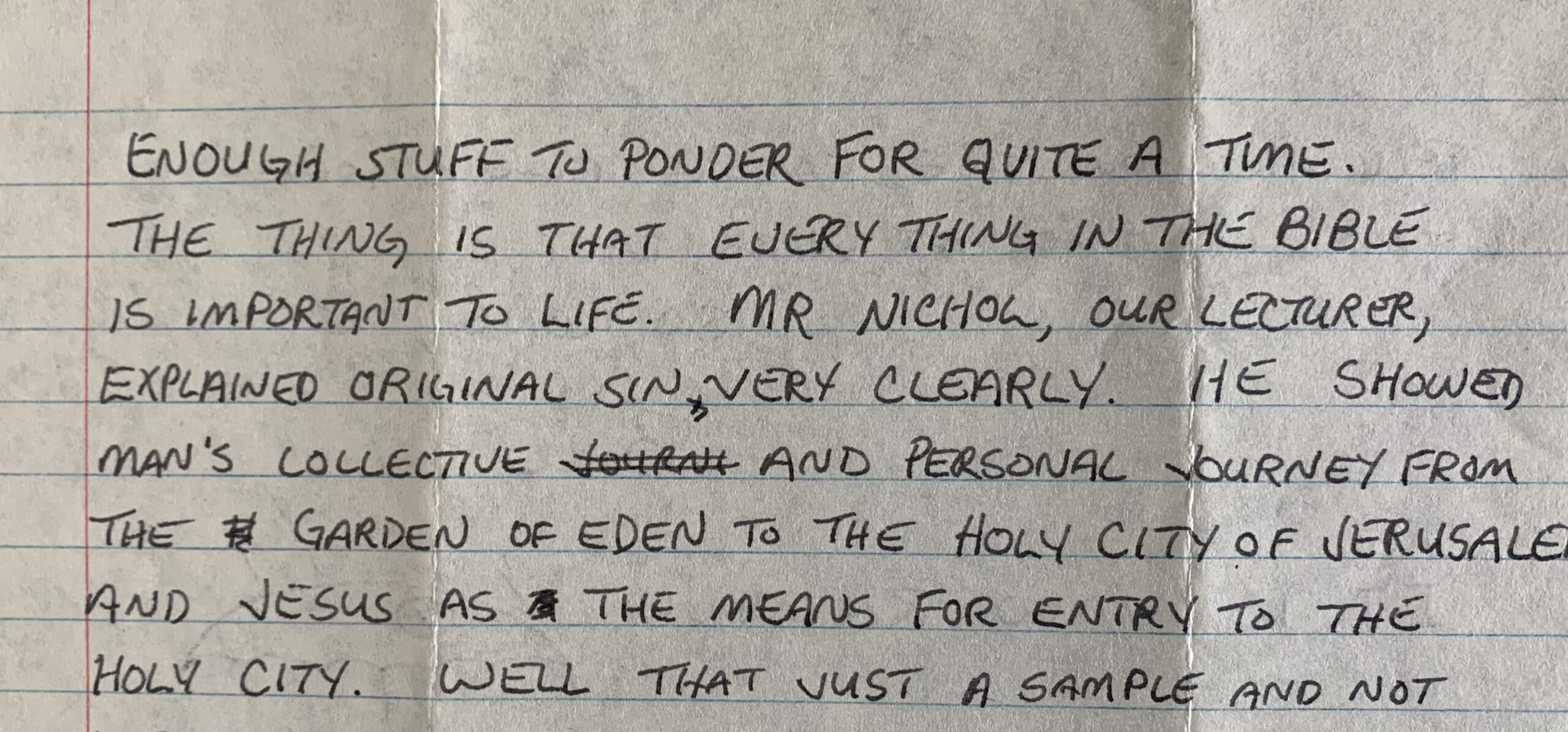

“We’ve been doing the Bible. I just finished a paper on a part of Matthew. I’ve also been reading a lot of the Bible myself. I just finished Acts. It’s really an incredible book. The Old Testament is much deeper than I suspected. Just Genesis has enough stuff to ponder for quite a time. The thing is that everything in the Bible is important to life. Mr. Nicholl, our lecturer, explained original sin very clearly. He showed man’s collective and personal journey from the Garden of Eden of the Holy City of Jerusalem and Jesus as the means for entry to the Holy City. Well, that is just a sample and not well explained here.”

World Civ discussions were had in small groups led by grad students. Other than a possible “hello” as I may have encountered Mr. Nicholl walking across campus, I hardly knew him. He returned to the U.K. when the tenured professor’s sabbatical was over at the end of the academic year.

Donald Nicholl, PhD, is listed in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. His entry reads, “Donald Nicholl (23 July 1923 – 3 May 1997) was a British historian and theologian. A speaker of medieval Welsh, Irish and Russian, he published books on medieval and modern history, religion and a biography of Thurstan. He has been regarded as ‘one of the most influential of modern Christian thinkers.’”

His obituary in the U.K.’s Independent newspaper added, “Donald Nicholl was one of the most widely influential of modern Christian thinkers, a teacher and writer whose words have inspired people in many countries and churches, and someone whose personal life wonderfully reflected his beliefs.”

A guest lecturer at a state university. I had nearly forgotten the way God used Mr. Nicholl, one of the most influential modern Christian thinkers, and his lectures as part of my effectual calling.

“The thing is,” my eighteen-year-old-self wrote, “everything in the Bible is important to life.” I would not have written that during fall quarter 1969.

Thank God for using a saint I hardly knew as a means of his grace in my life.